Kamal Boullata, Between Exits: Paintings by Hani Zurob. London: Black Dog, 2012

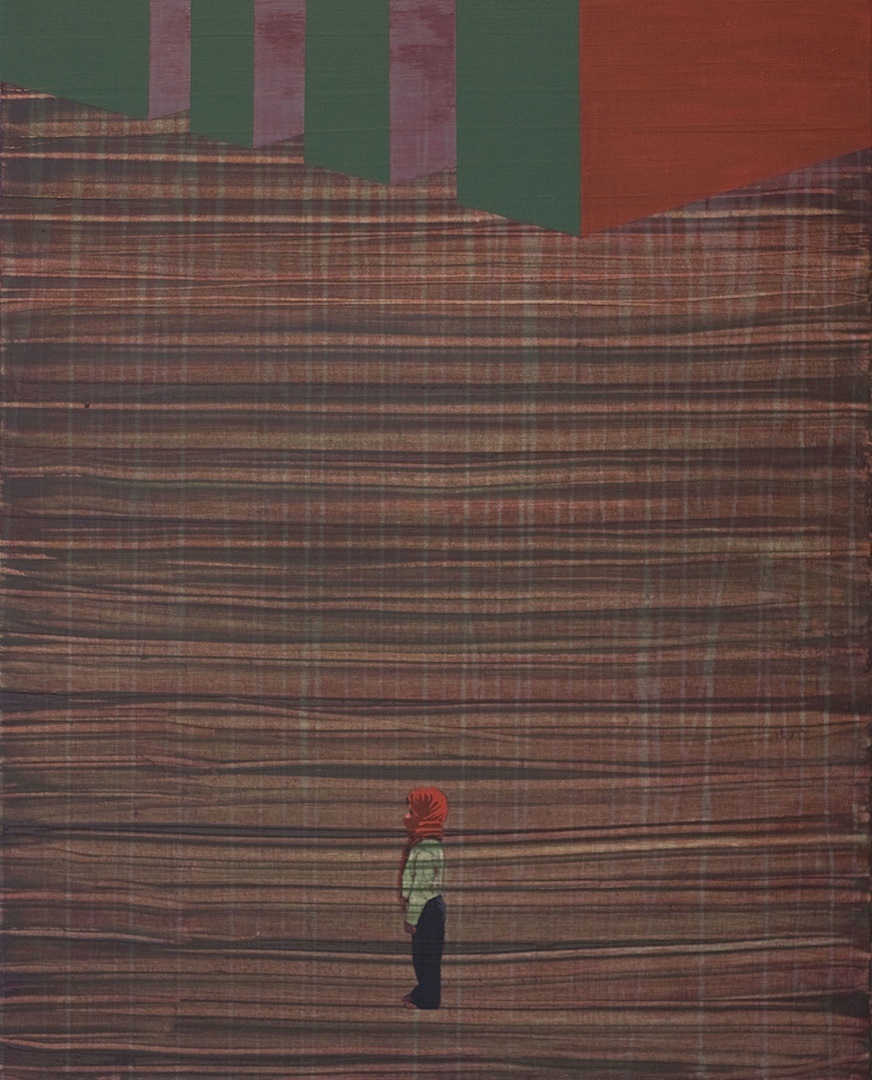

Hani Zurob’s early paintings are dominated by enigmatic figures of various shapes and sizes. Some resemble human subjects and are scaled to occupy the foregrounds of compositions—as though walking in a procession—while others are colossal and misshapen, overpowering everything in their path. Indications of their environment are equally nondescript. Vertical lines further divide the picture plane where small compartments are outlined, creating a sense of distance. Are those prison cells tucked away into a corner of the painting or are they the stacked quarters of refugee camps with reference to the artist’s hometown in Gaza? One distinct aesthetic constant is a flattening of space with which time is assigned to subtle changes in perspective. Taking the lead are those small shadows in flight—it is with their story that he is most concerned. What makes these works so important to the painter`s development is that he appears to have been in conversation with a previous generation of Palestinian artists at the time of creating them.

.jpg) [Hani Zurob, untitled (2001). Image copyright the artist. From the exhibition "Williamsburg Bridges: Palestine 2002."]

[Hani Zurob, untitled (2001). Image copyright the artist. From the exhibition "Williamsburg Bridges: Palestine 2002."]

For many artists born in the first half of the twentieth century—who marked the transition of Palestinian art from the modern period to contemporary visual culture—communicating the loss, displacement, fractures, and uncertainty of 1948 (and 1967) was a matter of urgency in the face of immediate erasure. Ismail Shammout, Mustafa al-Hallaj, and Abdel Rahmen al-Muzayen, for example, are identified as part of a core group of artists that worked closely with national political movements while embracing popular symbols as the visual material of collective memory and resistance. Overlapping with this specific school towards the end of its prominence was another set of artists that moved away from a reliance on overt symbolism when working just after the first Intifada by abstracting and decentralizing figures and dissolving landscapes and horizon lines. Fragmenting compositional space, they rendered the rapid deterioration of life in occupied Palestine. A number of artists during this second wave of post-Nakba art utilized media derived from natural resources in protest of the occupation with a boycott of Israeli goods. By experimenting with mud, wood, natural dyes, and leather in painting, sculpture, bas-relief, and installation while indirectly challenging their own uses of conventional aesthetics and popular imagery, Suleiman Mansour, Tayseer Barakat, Vera Tamari, and Nabil Anani (among others) steered contemporary Palestinian art in new directions.

Kamal Boullata’s Between Exists: Paintings by Hani Zurob traces the artistic career of the painter from his time in the West Bank—with a brief stay in Nablus then a longer period in Ramallah—to his current residence in Paris. The author begins with a description of Zurob’s childhood in Rafah and his family’s history in the surrounding area before delving into his arduous journey of moving to the West Bank and becoming a painter with little educational resources and few opportunities. Here is where Boullata begins a book-long disservice to Zurob, as he proceeds to situate his artistic training in Palestine as plagued by a dismal art historical trajectory and a lack of aesthetic stimulus. This argument is made in the preface of Between Exits and is reiterated throughout the monograph with frequent references to Palestinian “cultural ghetto[s]”—be it the Gaza community where Zurob spent his childhood or local art scenes in general. Boullata’s introductory description of Zurob’s significance as a young painter is set against “a homeland enduring over 40 years of military occupation, where art is saturated with nationalist clichés and tired iconographic images.”

While the author never minces words when condemning the Israeli occupation or pointing out the ineffectiveness of Palestinian political leadership, he also expresses a clear disdain and disregard for the artistic production that resulted during the latter half of the twentieth century in the West Bank and Gaza, particularly the “[Ismail] Shammout school of painting.” The downside of this cynical slant is that it creates gaps in Boullata’s analysis, which is otherwise interesting and informed. In addition to acting as an unnecessary distraction to the reader, this bias (with which he slips into art criticism) seems to prevent the author from offering an objective and cohesive art historical record.

[Hani Zurob, untitled (2005). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of Black Dog Publishing.]

[Hani Zurob, untitled (2005). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of Black Dog Publishing.]

Most unfortunate is Boullata’s overlooking of the indebtedness of Zurob’s painting to the second phase of post-Nakba art. Given that a central theme of Between Exits is the exploration of space in relation to the self amidst political conflict, displacement, and the “otherness” of exile, the author’s thesis would have benefited from a discussion of how certain 1990s works by Tayseer Barakat and Nabil Anani, for example, were visibly influential to the young artist`s early mixed-media paintings. Overtime, Zurob deconstructed these fragmented compositions as he moved to neo-expressionist self-portraits and abstract canvases that were, according to Boullata, first inspired by the stifling sense of immobility and confinement of life in Ramallah’s “bubble” and then later intensified when encountering a dark period of alienation in France. Although not included in the book, examples of Zurob’s early work show the bases for the palette and gestural style of painting that shaped his initial approach to portraiture and abstraction, which he eventually transformed in response to the aesthetic sensibilities of contemporary art in Europe and the spatial dynamics of life in exile.

[Hani Zuorb, "Heritage" (2009). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of Black Dog Publishing.]

[Hani Zuorb, "Heritage" (2009). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of Black Dog Publishing.]

[Hani Zurob, "Flying Lesson n. 7" (2010). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of Black Dog Publishing.]

[Hani Zurob, "Flying Lesson n. 7" (2010). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of Black Dog Publishing.]

Boullata’s dismissal of the formal progression of contemporary art in the West Bank and Gaza as he berates artists for forging a “culture of resistance” works to support the bizarre argument that Zurob’s formative years only began once he left the Occupied Territories. While frequently citing a (supposed) lack of aesthetics on the part of those who employed symbolic imagery, Boullata contradicts his own hypothesis by connecting Zurob to Palestinian peers who—although reflecting the leaps of today’s art with new media and updated technology—have built on the tradition of using metaphoric representation when exploring the many dimensions of the occupation. In the end, the reader is left wondering how an artist who is positioned as defying a “culture of resistance” can be simultaneously recognized as developing in concert with what appears to be the current incarnation of this very culture.